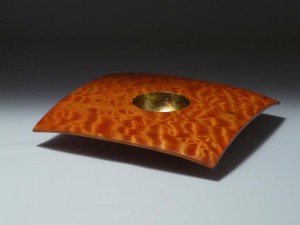

Tortured Sun Detail

I was queried by a few turners at the West Coast Roundup about the materials I use when colouring wood, so promised I would put something up. My plans for the future include posting something on coloring wood so I already had something in mind. Because it is a very extensive topic I would imagine it would best be presented in a series of smaller posts, so lets consider this the first post in a series that will stretch out over time. The best way to follow it will be to refer to the site map in the main menu.

First, I use dye for it’s transparency and occasionally paint if I am looking for something opaque. Dyes are totally dissolved in the carrier so do not hinder the passage of light the way a pigmented stain or ink will. Basically, dyes penetrate into the wood where pigmented colours remain on the wood. To emphasize this, the pigment settles to the bottom of my bottles of ink and stain while the dyes stay totally dissolved. For that reason dyes punch the chatoyance of figured wood and generally provide more vibrant colour while still letting the grain show through. “Tortured Sun” is a good example of that, however the effect still can’t be fully represented in a static photograph because the pattern changes dramatically depending on the angle of viewing.

Here are a few quick crib notes about dye. Aniline, dichlorotriazine and metal based dyes are most commonly used in colouring wood. I am presently using the Dichlorotriazine dyes (Procion MX) because of it’s vibrancy but am slowly switching over to the metal acid dyes because of their superior light fastness. More about that in a bit. Natural dyes like crushed blackberries and so on sound cute and “back-to-the-landy” but are not colourfast in the least and quite honestly are very dull. Aniline dyes are organic based (read: petroleum based oxides). They at one time were used with an oil base as a carrier and gained a reputation for not being coloufast for that reason. The bottom line is this (and this from an on-line retailer of some very good colouring products): there are apparently very few aniline based dyes being used now. The vast majority are dichlorotriazine or metal acid dyes and he says that those that are touted as aniline are in all likely-hood one of the other two anyway anyway, simply because “aniline” is more familiar to most folks. I will look more into this.

Dyes are dissolved typically in water or alcohol. Both have advantages and disadvantages depending on what you’re trying to achieve. In other words they both are good mediums …depending. I prefer water because it is free and non flammable. As a matter of fact I recall using copious amounts to put fires out when I was a firefighter (sorry, couldn’t resist that). I can dilute it on the piece with more (cheap, non flammable) water if I want to. I can safely heat it to dissolve the dye more easily. Some folks get all bent about the fact that it raises the grain. So raise the grain first with some water, sand it off (not a bad idea anyway) then apply the dye. Once you raise the grain, it doesn’t happen a second time. I very often use more than one colour, sanding back all but the last application, so it is a non-issue in that case. I also use some premixed dyes that are alcohol based and like them very much, so it’s not like they don’t perform satisfactorily. In the safety department, remember that alcohol flames are very nearly invisible. Alcohol is also a very volatile liquid (vapourize [evaporate] very easily) with a broad flammable range. For all you non firefolks, that means it produces lots of vapours for fuel (only vapours burn), catches fire very easily and there is no warning that it is actually on fire. Other than that, no worries. 🙁

Dye concentrates come in dry and liquid form. The liquid is very easily mixed but the dry is not that bad either – just not super quick. You can vary the intensity by mucking with the concentrate/water (or alcohol) ratio. When combining colours you can premix dyes or mix them on the wood depending whether you want one colour or varied colours. The latter is where things get really creative and takes practice to get what you want. An interesting thing to have to deal with is the fact that the wood itself has a colour. That means you are combining colours whether you like it or not and it isn’t always what you expected, so you have to compensate for it.

Although not the most light fast dye (it’s still very good) I prefer Procion MX dyes for it’s brilliant colours. It is designed for colouring fabric and is actually a Dichlorotriazine dye, not metal acid or metal complex. When dying fabric there is a very involved process of stopping and fixing baths using salts, potash and other stuff which isn’t required for wood. The most important thing is that it is compatible with cellulose, which of course is what wood is comprised. Basically, put it on and you’re done (except for finishing). It is available through Opus but I get it at Maiwa, a fabric and fiber arts dealer. I would suspect that other art supply stores have it as well. I have recently discovered Wood Essence in Saskatoon. They are on line and the owner, Jeff Richardson, is very knowledgeable. I put Maiwa and Wood Essence’s URLs in the “links” in the sidebar. Wood Essence sells Colour FX liquid dye concentrates (and other neat stuff). The best thing is that they sell the only “black” black dye that I have found other than leather dye (awesome black but too hard to sand back – long story, wait for later). The significance is that blacks are usually very dark blue, so when combining colours on the wood using the “sanding back” technique, you don’t get the second colour with stunning black highlights. What you get is purple when applying red and green when applying yellow along with black highlights whereas with true black you get the true second colour that you added after the black. On the other hand if you are trying to get some rich, varied browns, using the blue-black then red and yellow (with selective sanding back between applications) you get some magnificent combinations on figured wood.

So there you are – quick and dirty. A few tidbits on colouring using dyes, however not much on application. Understand that applying the finish is also a large part of the process in bringing out the Wow! factor, so there is much more to this story. I hope you will find this interesting and watch for more on colouring wood some time in the future. In the meantime, try to find a book called Colouring Techniques for Woodturners by Jan Sanders. I picked it up more than 15 years ago from Lee Valley Tools but is out of now out of print. I have seen used copies available on line, however.

As always, I encourage your comments and questions, so please refer to the tag line at the bottom of the article to post a comment.

![pole_lathe[2]](https://edswoodturning.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/pole_lathe2-300x224.jpg)